Exhibition review of NUS Museum's 'Radio Malaya: Abridged Conversations About Art'

- kellykhua

- Nov 19, 2021

- 2 min read

Updated: Apr 29, 2023

Curated by Ahmad Mashadi and Siddharta Perez, Radio Malaya: Abridged Conversations About Art is aptly nestled in Singapore’s oldest university museum, whose roots harken back to art history’s local beginnings. The exhibition’s title alludes to the broadcaster of

S. Rajaratnam’s radio play, aptly capturing its themes of history and cultural independence. This idea of communication reinforces the museum’s framework of creating a dialectic between past and present, art and writing, to explore how Singapore’s contemporary art informs our understanding of its permanent collection.

With dialogue at the core, I was first greeted with an extract from Rajaratnam’s text where characters discuss the creation of Malaya’s history and identity for study. This conversation foregrounds the gallery’s chronological layout, which follows collections of premodern, modern, and contemporary Southeast Asian art that first curator, Dr. Michael Sullivan, believed were vital to teaching art history.

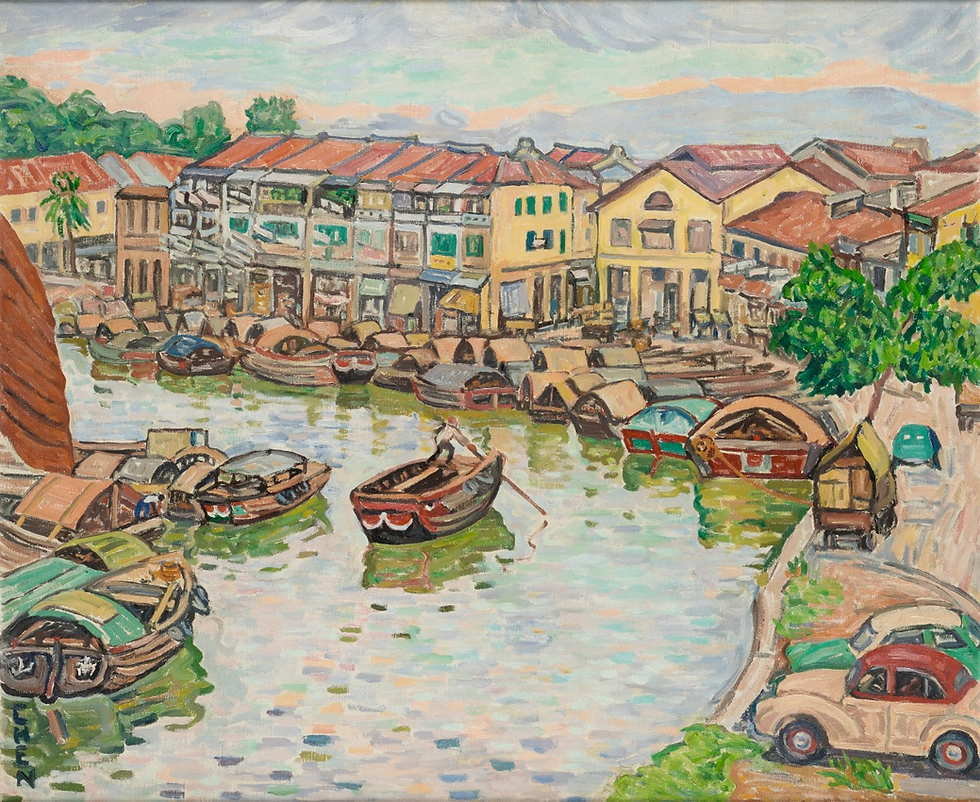

While excerpts from Rajaratnam’s radio play ran along one side of the gallery’s walls, the opposite end displayed a variety of sculptures from Hindu, Buddhist, and Islamic cultures with quotations from T.K Sabapathy’s scholarship on Southeast Asia’s art historiography. The subsequent section charted how modern Malayan artists synthesised Western art styles and responded to societal conditions, with paintings from Liu Kang to Jaafar Latiff epitomising art's transition from the figurative to the abstract.

The interaction of visual, textual, and auditory mediums made my visit informative and stimulating, but the absence of text labels and details in the exhibition catalogue complicated my appreciation of the paintings in salon-style hang. Nonetheless, the exhibition's selection of contemporary art impressed me as they collectively explored memory, space and documentation. Take for instance Debbie Ding’s ‘The Library of Pulau Saigon’ and furniture from Amanda Heng’s ‘Let’s Chat’. Both demonstrate how objects possess new meaning over time, transforming into art when in the artist’s hands. Like how Ding’s sculptures spotlight neglected ethnographic objects, Salleh Japar’s reconstructed ‘Cultural Sinkholes’ uncover how Singapore’s colonial history and racially segregated landscape influence our perceptions of race.

Personally, Herman Chong’s ‘Plants (Darkened)’ is a highlight that makes the exhibition come full circle. Inconspicuously placed along the dimly-lit corridor intersecting ‘Wartime Artists of Vietnam’ and the exhibition’s entrance, these seven black, ready-made trees cause visitors, including myself, to mistake it as decoration before realising its status as art. ‘Plants (Darkened)’ thus made me realise how exhibition design largely affects my encounter with art. In conflating nature with artificiality, Chong’s work speaks to Japar’s white paper mache sculptures from the exhibition’s beginning. Considering these two monochrome colours that are evocative of binaries like life and death, the exhibition’s conclusion conjured up a contemplative mood that probed me to think about Singapore’s art history.

Meditating on Chong’s work, I was reminded of T.K Sabapathy’s haunting conclusion in his black book, Road to Nowhere: the local practice of art history remains “entombed...in the 1960s”. Whether this rings true today is questionable, but just like how there is a single spotlight shining down on one of Chong’s trees, perhaps there is a sign of hope.

Comentarios